Michael Wesch's article “Anti-Teaching: Confronting the Crisis of Significance” focuses on the most crucial problem that modern educators face: student’s don’t see the importance of education. He describes a population of students that are going through the motions. They attend class, collect information, and ask “administrative questions”. Part of the issue is the way schools and classrooms are structured. Students are conditioned to believe that learning requires a more rigid process, where creativity is not nurtured and the most important thing is the grade. Wesch argues that in order for students to find meaning in their educations, teachers need to create learning environments that inspire deep questions and allow students to pursue what they really want to know. The focus should be on learning and how students navigate this process, rather than on “teaching” that aims to cram knowledge into their brains. This type of education requires rethinking our educational spaces and finding what motivates students.

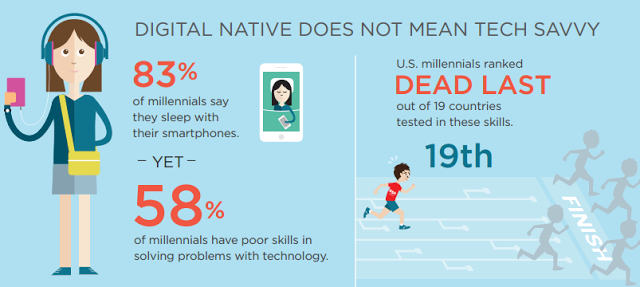

The discovery of motivation is often complicated by the modern era of cell phones and other technologies. Sherry Turkle’s article “The Flight From Conversation” outlines how people have lost the ability to connect and communicate face to face, which are two crucial aspects of the learning that Michael Wesch describes in his own work. In comparing the two articles, I thought about how we responded when Kelly Reed asked us to find the answers to five questions. With laptops in front of us, we worked silently and individually, not even acknowledging those around us. We modeled the type of society that Turkle is describing, participating in a way that is the exact opposite of what Wesch would want. In that moment, “we are together, but each of us is in our own bubble, furiously connected to keyboards” (Turkle). What is most interesting, and disheartening, is that we did this by default. Individual achievement is so ingrained in our value systems that most of us probably didn't even consider asking someone else for help. We took on the task as our own, and though we acquired knowledge, did we really learn? Luckily, as we become aware of this as educators, we can influence a new generation of learners to move away from this type of classroom participation (if you could call it that).

Though the topics seem very different at first glance, underlying both Turkle and Wesch’s ideas is the need for human interaction. Turkle wants us to have conversations while Wesch wants us to ask questions. By asking our questions, we are able to create conversations that lead to meaningful exploration and learning. Allowing these conversations into our classrooms will (fingers crossed) help students recognize the significance of their learning, and can drive curiosity and motivation.